GLOBAL learning was on the agenda when Lewannick Primary School played host to the former bodyguard of ex-South African leader, Nelson Mandela.

Chris Lubbe grew up in a shanty town in Durban, South Africa, at a time when apartheid was at its height. He ended up working as the bodyguard of the revolutionary president of South Africa throughout most of the 90s, entirely through chance. His journey is one of fear, courage and, ultimately, forgiveness.

He was welcomed to Jericho’s Kitchen in Launceston on Friday, July 7, to speak about his experiences and impart the wisdom he gained from working alongside one of the greatest men in South African history.

Lewannick Primary School hosted the event as part of its involvement with the Global Learning Programme (GLP) in England. The school has been an ‘Expert Centre’ for the GLP, which is a programme of support that is helping teachers in primary, secondary and special schools to deliver effective teaching and learning about development and global issues at Key Stages 2 and 3.

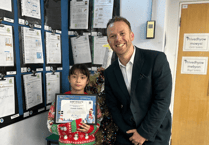

Headteacher of Lewannick Primary School, Ben Towe, said he was ‘delighted’ to welcome Chris to talk about his experiences, which he hoped would be of benefit to teachers and pupils alike. Earlier that day Chris had taken an assembly at the primary school.

Mr Towe said: “It is great to have Chris in for assembly this morning; he spoke to our Year 5 and 6 pupils and to hear their responses was great. That is what this is all about really, it isn’t just learning about Africa, it is about enquiry, getting pupils to engage with a topic and look at it critically. For example we want children to be able to look at a newspaper and see that is only one interpretation of events, whereas someone’s personal view, like Chris’, could be completely different!”

Chris began his talk by offering the audience an insight into his background.

He spent his youth growing up in the ghetto, where life was difficult, facilities were limited and education was poor. He found himself at the centre of a world that believed ‘white’ and ‘non-white’ people should be segregated, leaving him to question who he was and where he fitted in society.

In apartheid South Africa, people were classified by the colour of their skin, and that determined what kind of life they would lead. Everything was segregated by ‘colour/race’.

Chris said: “In 1948 an act of parliament led to the introduction of apartheid classification. I was classified as ‘coloured’. I was born into a system that said if you were not white you would not succeed and that gave me a hunger for education — I was determined to make something of myself.”

However, getting an education as a black or coloured person in South Africa at the time was a very difficult thing to do.

Schools were separated by colour. Chris said the government refused to supply books to any of the ‘black schools’: “Education was used as a tool to repress people. We had 60 children in my class. Learning as a child was hard.”

Chris explained that the only access he had to books as a child was by visiting the local dump and picking through the rubbish to find them.

He said: “I remember Romeo and Juliet was my first book, I took it home, cleaned it up and read it from cover to cover. I ended up finding over a thousand books. Even then I was fighting the system in order to gain a better education.”

During Chris’ youth there were many anti-apartheid rallies and protests, which inevitably ended with protestors being shot at with real bullets and tear gas.

While attending school, Chris remembers being told he was ‘too young to take part in protests’ but that he and his friends could have their ‘own kind of protest’ by writing letters to world leaders.

Organising themselves, each child chose a world leader and asked for their support to stop apartheid. Chris chose Queen Elizabeth II. He said: “We sent these letters off and waited for a reply. One never came. It was at that moment I thought people don’t care about us, the only way to change things is to do it myself!”

It was many years later whilst attending an event at Buckingham Palace with Mandela that Chris discovered the Queen had in fact responded. Whilst on duty, Mandela called Chris over and the Queen presented him with the original letter he had sent when he was nine.

He said: “She asked me if I got her reply, I said no and she produced a copy of that letter. At the time the state was opening up letters and destroying anything to do with anti-apartheid activism. I was really pleased to read that letter, I really felt like I had come full circle.”

Chris has had many life changing experiences throughout the years.

At the age of 14 he found himself in prison, then after failing to get a job as a pilot he began working as a ‘trolley boy’ on the trains with his uncle. He watched as a black man, he had innocently helped onto the ‘white only’ carriage, was thrown from it whilst travelling at high speeds by two policemen. He said: “If my uncle hadn’t come when he did I would have been thrown off too!”

He later ended up in Pollsmoor prison for his involvement in the peaceful protests and activist work being carried out across South Africa. Whilst in prison he claimed he was waterboarded twice a day and tortured for weeks at a time, being forced to stand under a cold shower without food and was even involved in a game of ‘Russian Roulette’. He said: “I remember thinking the bullet was in line and contemplated turning the gun on them. I decided to be compliant. Thinking ‘this is it’, I pulled the trigger and…the gun seized and jammed. I took that as a sign from God that I still had more on this earth to do!”

It was some years later when Chris found himself in the employment of Mandela. Chris was 28 when Mandela was released from prison.

He said: “It was actually by chance. When he was released from prison I was in Cape Town. I was in charge of IT for a music concert for the African National Congress. Mandela called up before the show and said he wanted to talk to the head of IT — that just happened to be me.

“I spoke with him and he explained he had an emergency and that I was to come to his office. I was given a time and a place and was expected to turn up — well, you don’t exactly say no to Nelson Mandela, do you!”

He recalled the first thing Mandela said to him: “As soon as I walked in he didn’t say hello or greet me at all, his first question was ‘how tall are you?’ I was shocked at this but answered ‘6”3’. He asked my shoe size. I answered ‘14’. He replied ‘you are just the man I need’.”

Chris then embarked on a ten-year career as one of the leader’s bodyguards — receiving SAS training.

During his time spent with Mandela, Chris had the opportunity to meet many influential and powerful people. He met Fidel Castro, Bill Clinton, Mick Jagger, Phil Collins, shared a dance with Princess Diana, had dinner with Jay-Z and Beyonce and met Pope John Paul II, who told Chris he would ‘make a good speaker one day’.

Chris was also lucky enough to be mentored by South African social rights activist and retired Anglican bishop Desmond Tutu.

Chris said he learned a lot about himself whilst working with Mandela. He recalled how he had to ‘learn forgiveness’ and work alongside his former torturer — a white South African bodyguard who had been employed by Mandela following the end of apartheid.

This man had been an officer at Pollsmoor prison. At first he didn’t believe he could ever forgive this man. He said: “I was so angry, I wanted revenge.

“Nelson Mandela took me to one side, sat me down and told me I needed to forgive this man. He said if he could forgive the people who imprisoned him for 27 years I could forgive this man. I really didn’t think I could.

“He asked me to write down everything I was angry about on a piece of paper and burn it.”

Chris said by the end he had needed a whole book not just a page. He added: “It took me a long time to forgive this man but we now talk every week and I am godfather to his son. It proves forgiveness does work — forgiveness is a choice and a journey, something we all must learn.”

Chris wanted to get across to those present that it is important these lessons of forgiveness are taught to the youth of today.

He said: “Nelson Mandela was like a father to me, he taught me this: ‘Ubuntu’ — it means ‘I am because of you, you are because of me, together we are’.”

He explained that this was something schools needed to focus on when teaching pupils, a sense of togetherness and unity.

He concluded: “Sadly we live in the world of data and ‘raised online’ where it becomes all about how we must do things. Focus has been taken away from the whole child. We no longer teach the whole child because the process gets in the way and we need to get out of that habit.”

All present thanked Chris for an illuminating talk and were left in awe of a man who has accomplished so much, despite the adversity he faced under a system that said he wasn’t worthy of an education.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.